General Electric has already pledged to reduce their carbon footprints by 20 percent by 2020

President Donald Trump may be dragging out his decision on whether to ditch the Paris climate agreement, but major American corporations have not waited for a government signal to start cutting their carbon emissions.

Before Trump had even raised the possibility of scrapping US involvement in the landmark 2015 treaty, Coca-Cola and the engineering giant General Electric already had pledged to reduce their carbon footprints by 25 percent and 20 percent, respectively, by 2020.

Apple meanwhile boasts of running its US operations on 100 percent renewable energy.

"We believe climate change is real and the science is well accepted," GE's CEO Jeff Immelt said last month, offering a stark contrast to an administration that features prominent climate change deniers.

Agribusiness giant Monsanto told AFP it was "committed" to helping "farmers adapt to and mitigate climate change."

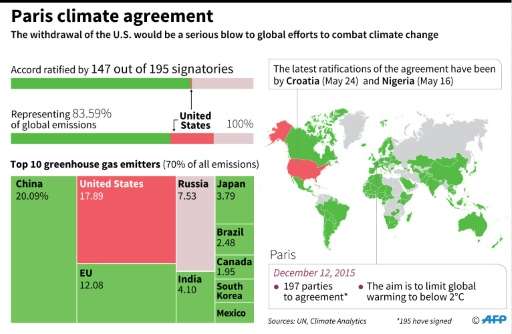

Even energy-sector heavyweights—those who seemingly have the most to lose from tougher environmental rules—are joining the trend started by the Paris Agreement, which aims to keep global warming "well below" two degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels.

Oil giant Chevron "supports continuing with the Paris Agreement as it offers a first step towards a global framework," spokeswoman Melissa Ritchie said.

Rival ExxonMobil recently implored the White House not to exit the climate treaty in order to respond effectively to climate "risks."

General Electric has already pledged to reduce their carbon footprints by 20 percent by 2020

Shifting attitudes

Just a few years ago, the US business world was using all its weight to impede climate talks, notably leading to the collapse of a 2009 summit in Copenhagen.

But many companies now find their image at stake in the United States, where opinion polls indicate the public are concerned by global warming and want to remain in the Paris agreement.

While growing environmental awareness has played a role, corporate America's conversion is not solely the result of do-gooder impulses.

"The companies are increasing their commitments in the climate area irrespective of (Trump's) decision, because it saves them money, it reduces their risks and most importantly, it's a massive market opportunity," said Kevin Moss of the World Resources Institute.

The bottom line has indeed shifted for businesses. Major investors are exiting fossil fuels and companies are facing increasing pressure to adapt their growth models to a world without carbon.

"Our customers, partners and countries are demanding technology that generates power while reducing emissions, improving energy efficiency and reducing cost," said GE's Immelt.

Oil prices have fallen through the floor in recent years, with a barrel of benchmark crude hovering around $50, down from more than $80 a decade ago. As a result, investing in the sector is much less profitable.

As a sign of the times, Exxon shareholders on Wednesday voted to force the company to factor in tougher climate policies on emissions and disclose how they may affect company revenues.

Oil giants ExxonMobil and Chevron recently came out in support of the Paris Agreement, with the latter going so far as to beg the White House to not exit in order to respond to climate "risks"

Structural changes

Trump also has pledged to revive the coal industry but given the boom in natural gas, which produces 50 percent less carbon dioxide and is far cheaper than coal, most experts say that will be difficult to accomplish on a large scale.

Still, fracking, or hydraulic fracturing—a principal means of natural gas extraction—also faces stiff criticism for its environmental impacts.

The costs of renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar power, also have come down sharply, thanks in part to investment and public subsidies that have made the sector more attractive.

Melissa McHenry, a spokeswoman for the major US generator American Electric Power, said her company had diversified into renewables and was investing "in renewable generation and other innovations that increase efficiency and reduce emissions."

Lynn Good, head of Duke Energy, told The Wall Street Journal that "because of the competitive price of natural gas and the declining price of renewables, continuing to drive carbon out makes sense for us."

There is still skepticism in certain quarters, particularly on the costs of climate policies.

The American Petroleum Institute, an industry body representing 625 businesses, is wary of "government mandates that could increase energy costs," according to spokesman Eric Wohlschlegel.

But Moss of the World Resources Institute said withdrawal from the Paris accord will not stop the momentum, and companies will continue down their current path "even without it, because everybody else is doing it."

"The only countries we'll be in the company of if we pull out are Syria and Nicaragua," he said.

© 2017 AFP